Image only for representational purpose

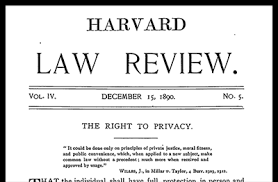

In this series of blogs, we have been exploring the theoretical foundations of informational privacy. In the last post, we examined Helen Nissenbaum’s very influential construction of privacy as ‘contextual integrity’. In this post, we will turn the clock back a century or so to examine one of the most influential legal developments in US privacy jurisprudence – which, as it happens, was neither a statute nor a Supreme Court judgement, but a law review article – ‘The Right to Privacy’, written by Samuel Warren and Louis Brandeis in the Harvard Law Review, in 1890.

In what has been termed (by scholars of US law) as the ‘most influential law review article ever written’, the two authors examined the growing unease over the technologies of ‘newspaperisation’ – widespread printing technologies and the rise of the photography, in particular – which were increasingly making intrusions into family and private life possible. To quote their particular concern – “[N]umerous mechanical devices threaten to make good the prediction that ‘what is whispered in the closet shall be proclaimed from the house-tops.”

Warren and Brandeis found that existing elements of tort law explicitly protected certain ‘material’ elements of personality rights – such as libel or defamation protecting against pecuniary harm and losses, or copyright protecting the right to withhold publication. To look for the legal foundations for a new ‘tort’ of privacy, they turned to English common law, which had, through reading in implied terms in contract law or extending copyright law into elements of protecting personality and publicity rights – had implicitly created the legal basis for the judicial recognition of immaterial rights or the legal protection of ‘affect’ or emotion. In particular, the authors argued that copyright law and protection of immaterial aspects of property respects the ‘thoughts, emotions and sensations’ encompassed within those forms.

However, the law did not explicitly provide protection for emotional or ‘spiritual’ harms arising from intrusions into aspects of an inviolate personality. Nor was the extension of immaterial rights into what would be recognised as ‘privacy’ consistent. They argued that protecting privacy required explicit recognition of emotional harms and a recognition of the ‘right to be let alone’ – a recognition of a zone of ‘inviolate personality’ of the individual, and the right to control for oneself one’s ‘thoughts, communications and sentiments’. Privacy, thus conceptualised, has an intangible, incalculable ‘affective’ or emotional component, not entirely captured by the protection of personal property.

Warren and Brandeis’ article has been one of the most influential formulations of the law of privacy, not least because Louis Brandeis went on to become a Supreme Court justice and directly charted the course of US privacy jurisprudence. The article, in fact, maybe one of the most influential law review articles in Indian privacy jurisprudence as well – having been cited and discussed in Gobind v. Madhya Pradesh and Naz Foundation v. Govt of NCT of Delhi, which were an early elaboration of the right to privacy in India, and subsequently engaged with extensively in Puttaswamy v. Union of India.