Image courtesy: Geo-spatial World(Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license)

As the Corona pandemic rages across the world, another scourge has gripped the internet ever so strongly – misinformation. The hard task of fighting misinformation has become even harder as the human content moderators are forced to sit at home due to the outbreak. Privacy-related restrictions mean that such moderators are unable to work from home and Artificial Intelligence has taken over the bulk of the work. This, in turn, is leading to arbitrary moderation of even content which is legitimate.

Content Moderation and Fundamental Rights

Although the present outbreak may have cast a spotlight on the content moderation practices of internet platforms, this is by no means a new problem. In the context of India, it is well-known that uneven enforcement of internal hate speech standards often results in discrimination against particular communities, especially minorities. Moreover, by acting as proxies for the State in content filtering and internet shutdowns, these information intermediaries often impose horizontal censorship on free speech.

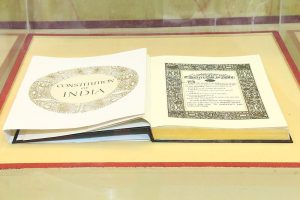

Such uneven enforcement of hate speech standards, as well as censorship, potentially implicates various Fundamental Rights (FRs) guaranteed under Part III of the Constitution of India.

Despite their impact on FRs, not much has been done by way of legislative interventions to regulate the functioning of internet intermediaries. Instead, this void is currently filled through the judicial route. An instance of this was the writ petition filed in the Delhi High Court against the change in the ‘Terms of Service’ of WhatsApp, on the ground that it violated the users’ right to privacy. Even though the High Court prohibited WhatsApp from sharing data of those who wished to opt-out from the changed Terms, it specifically noted that no writ, as sought by the Petitioners, will lie as the Terms of Service did not emanate from a statute.

The Court, though, did not bother to clarify on what basis it then issued these directions. The matter is now pending on appeal before the Supreme Court and Facebook (WhatsApp’s parent company) has challenged the jurisdiction under which the High Court issued these directions.

Application of Fundamental Rights against Private Entities

The WhatsApp litigation provides a crucial clue on what may impede the enforcement of FRs against private entities, including internet platforms, in India. For one, approaching the Supreme Court under Article 32 is traditionally understood to be possible only against State action. Similarly, even the Article 226 route, which gives High Courts a wider latitude to enforce both Fundamental and other legal rights, is only available against entities discharging a public function. Whether internet platforms discharge a public function is an unresolved question.

Despite these reservations, parties aggrieved by private entities should be able to enforce their rights either under Article 32 or Article 226, at least in some instances. This is for two reasons: one, more and more FRs are now recognized as having a horizontal application, ie, they may be claimed against private entities. This is over and above those FRs – Articles 17, 23, etc. – which have been traditionally understood as applying horizontally. Thus, depending on the right violated, parties may directly approach the Supreme Court.

Two, given that most, if not all, internet communication platforms perform a valuable public function in a democracy – they enable effective political participation through the dissemination of ideas in the public sphere – they should be amenable to Article 226 jurisdiction as well.

Conclusion

The rise in the power of private corporations has meant that they routinely come in conflict with individual rights. Although the traditional framework may not allow Constitutional Courts to assert their jurisdiction, there is sufficient wriggle room under Indian law, which should allow for this. A failure to utilize this may lead to the negation of FRs.